Ministers are demanding a return to normal, while universities are using an ever-greater range of technologies to support students – but what do those doing the teaching make of it all? David Kernohan has data from a new survey.

There’s been a marked shift in the place of teaching quality within policy making – once something we encouraged and supported to do, teaching quality has become something we do to academics.

For this reason, it was a delight to get 372 responses to our recent survey which presupposed a degree of agency in quality for academics. Kortext – who commissioned the survey from us, obviously has a particular interest in the impact of learning resources and learning technology on teaching quality – and beyond this, there is also a chance to hear seldom-heard academic voices on teaching quality.

What’s the use of experts?

National policy usually happens at the level of the institution or (broad) subject area. Despite suspicions otherwise, the days of direct state interest in what happens in the lecture theatre are beyond us – unless one of the ever-shifting lines of the perpetual free speech panic is crossed and the media circus begins again.

The much-vaunted teaching excellence framework (TEF), and much of the current trends in quality assurance are currently focused on output metrics. Teaching must be good, runs the argument, if students stay on the course and get good jobs at the end of it. Quite what the teaching needs to be like to ensure these outcomes is unclear – the 00s emphasis on encouraging the enhancement of teaching practice has given way to a focus on punishment and on public shaming.

Another pressure on teaching practice comes from some of the wider fancies of the education technology industry – we are always on the cusp of some digitally enhanced revolution, meaning that current practice is generally dismissed as old-fashioned, dull, and doomed. In the continued absence of the virtual reality wonderland we have been promised since the 90s the lived reality of lectures, seminars, reading lists, and laboratories has not changed substantially.

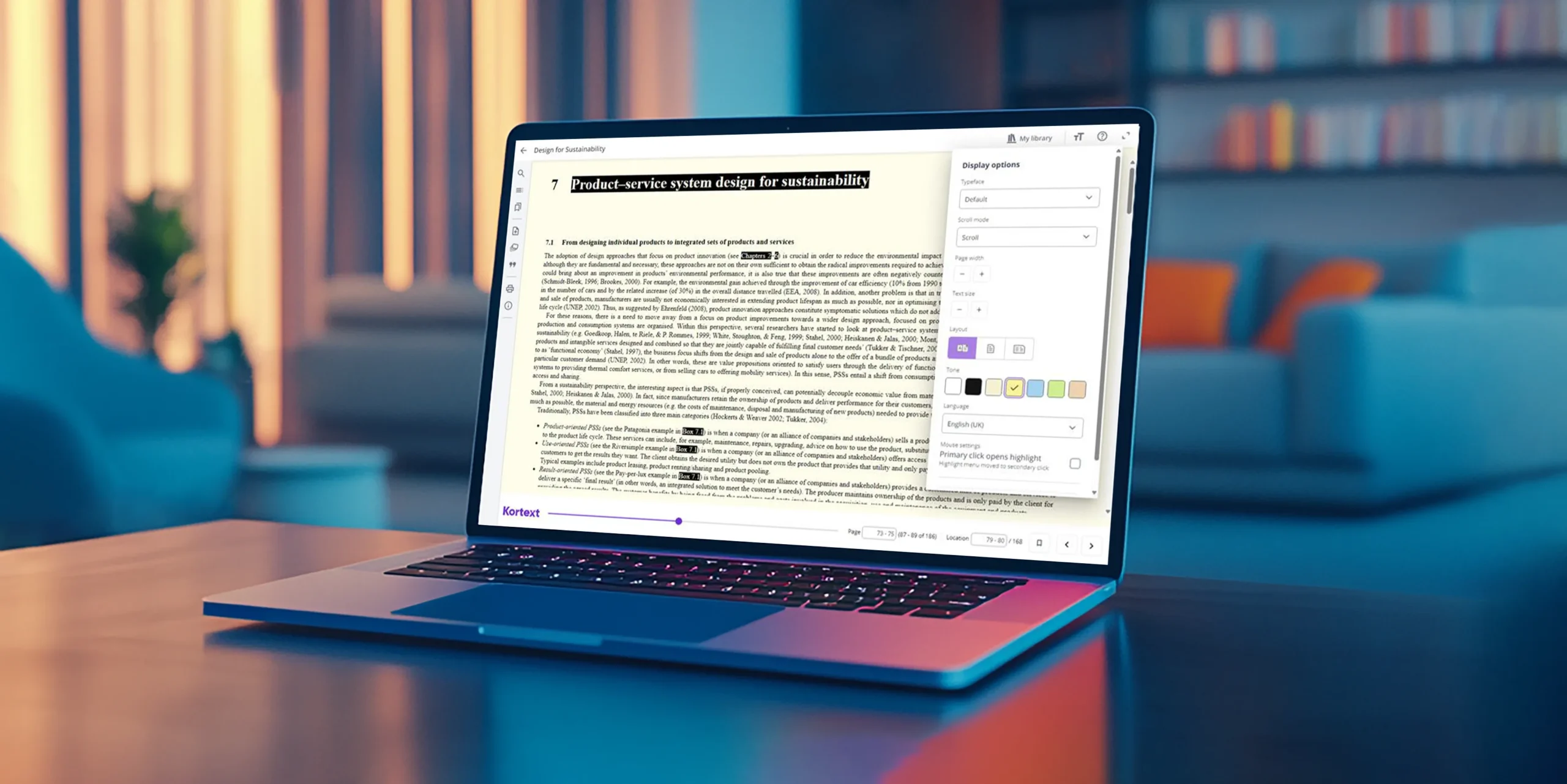

Digital learning resources – from ebooks to the virtual learning environment (VLE) – have made some inroads. Certainly the tools exist (if properly deployed and configured) to make the administrative end of the student experience simpler. Notes, slides, and readings are downloadable at a single click – a missed lecture means a video recording rather than your housemate’s notetaking, and the library now begins in your browser. The “real educational technology” of enterprise systems is gradually improving.

Thus far these are all hygiene measures – great for the overall student experience, leaving more time and capacity for learning. And the use made of these resources can be correlated with attendance and other measures to identify and support students who may be struggling far quicker than before.

But what do academics make of all this?

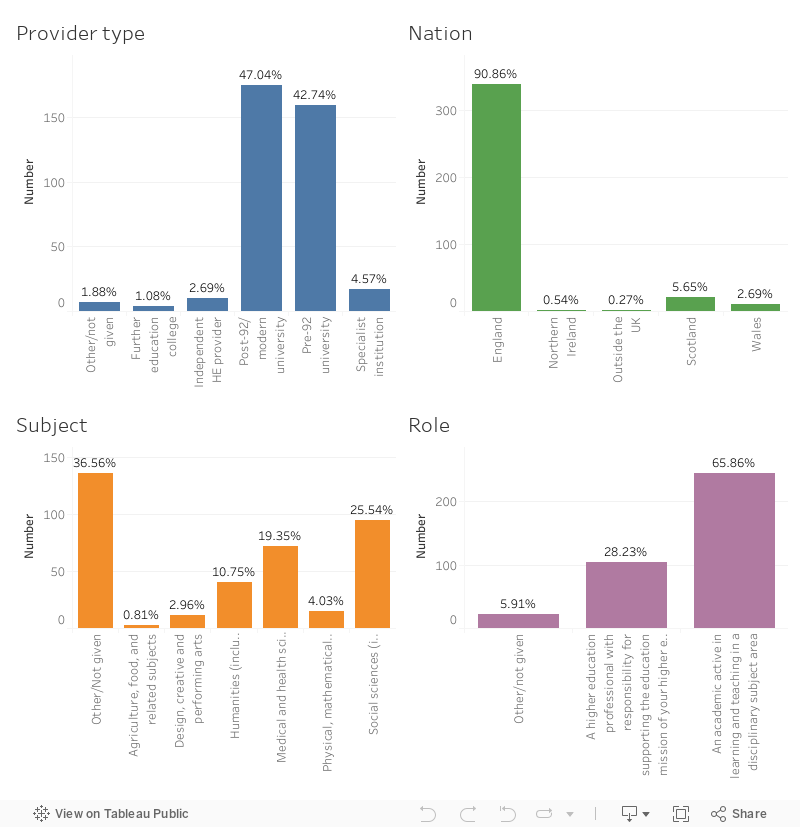

Meet the sample

This is a self-selecting online sample, with responses collected between late April and late May this year. Of the 372 recorded responses around 89 per cent are from a large, traditional-style, university. The majority (91 per cent) were from England – two-thirds were academics active in teaching within their subject area, and the remaining third could be characterised as having a more explicit learning support role.

Teaching through Covid

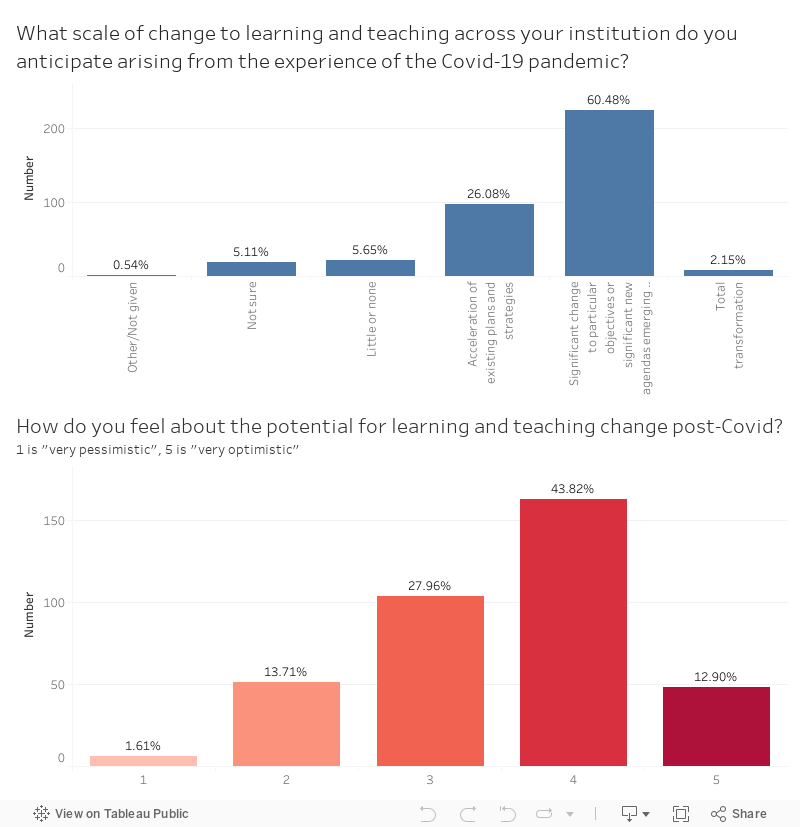

We’re still in the middle of a pandemic, though nearly all restrictions on activity have now been abandoned. Clearly the experience of the emergency pivot to online still looms large in the academic consciousness – these, after all, are the people that made remote learning work in those dark days. As a result, it is not surprising to find 6 in 10 respondents anticipating significant new changes to teaching within institutions, with a further quarter expecting the acceleration of existing plans for change.Asked to rate their optimism on the potential for change, we see a cautious optimism in our sample with 44 per cent scoring their optimism as 4 out of 5. A further 27 per cent equivocated with a score of three.

[Full screen]Why the difference? The free text responses suggest we are seeing a qualifying of potential given the politics (small- and large-P) at play. As one respondent put it:

A cultural shift in digital technology adoption and openness to new ways of working and studying. The main risk is government interference with learning and teaching to dictate how students should learn.”Institutional managers are often lumped in – or perhaps more accurately – seen as cowed by the ministerial insistence on the “old normal”. And with waves of staff redundancy already being felt around the sector it is difficult to feel optimistic about anything, despite a palpable pride in what the sector learned during emergency remote learning and a clear sense of some of the opportunities on offer.

However, a minority are sceptical about the role of technology in teaching itself – there are concerns about the validity of remote and online assessment, and about inequalities in access to the digital tools and connectivity a more technology-based approach would need.

Making change

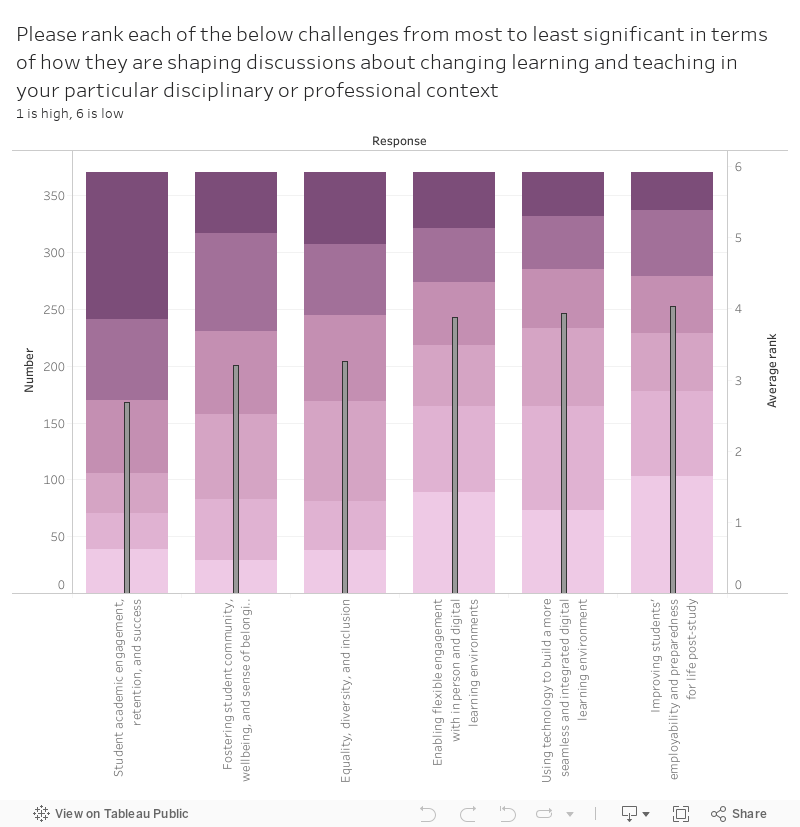

We asked our sample a number of questions about the way change happens in teaching. On what shapes discussions the ranking answer (an average ranking of 2.69 of 6) focused – as you may well hope – on student engagement, retention, and success. The mere capacity of technology for integration ranked on average 3.93 of 6, with flexibility doing slightly better (on average 3.26 of 6).

[Full screen]In other words – changes to teaching are overwhelmingly considered on the basis of the benefit to the student experience before any other considerations come into play.The “other category” was interesting here – clearly there is a lot of engagement with the employment skills agenda, and there was a great deal of interest in issues around mental health and wellbeing for staff and students (one perfect response was simply stated: “compassion”) which sat uneasily besides regulatory pressures on contact hours and provider constraints on staffing and funding.In terms of areas of practice the biggest interest was around assessment and feedback (71 per cent), far ahead of course structure (58.5 per cent) and the student voice (57.2 per cent). This choice of issues was overwhelmingly driven by student expectations (76.2 per cent) and government or regulatory policies (61 per cent).

[Full screen]In other words – changes to teaching are overwhelmingly considered on the basis of the benefit to the student experience before any other considerations come into play.The “other category” was interesting here – clearly there is a lot of engagement with the employment skills agenda, and there was a great deal of interest in issues around mental health and wellbeing for staff and students (one perfect response was simply stated: “compassion”) which sat uneasily besides regulatory pressures on contact hours and provider constraints on staffing and funding.In terms of areas of practice the biggest interest was around assessment and feedback (71 per cent), far ahead of course structure (58.5 per cent) and the student voice (57.2 per cent). This choice of issues was overwhelmingly driven by student expectations (76.2 per cent) and government or regulatory policies (61 per cent).

Making technology work

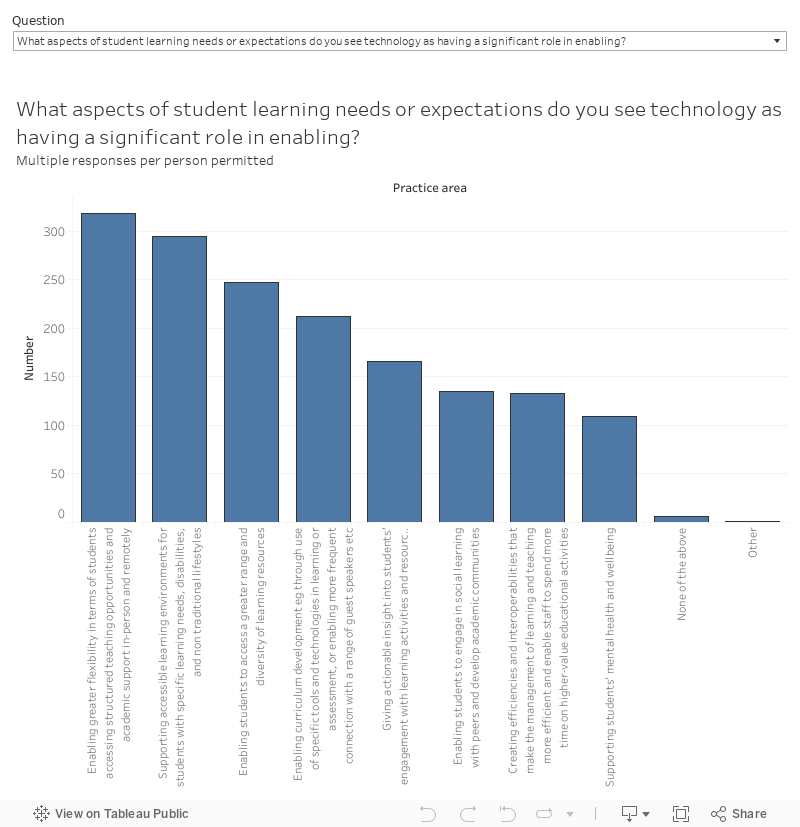

The value of technology was perceived as enabling flexibility of access to academic support (86.2 per cent for structured teaching, however accessed, and 79.7 per cent supporting students with specific needs). Access to a diversity of learning resources was a strong but distant third (66.8 per cent), with the wilder end of technological innovation falling further down – and supporting student mental health at the bottom.Those days staring at screens during lockdowns has had an impact on all of us – the hegemonic conflation of “wellbeing” with a break from screens means that even though the opportunities are there to at least target intervention and support it is unlikely to be the first thing you think of.

Getting there

Advance HE is the end product of a great deal of government investment in teaching quality enhancement. These days, it does its (excellent) work based primarily on subscription funding – but predecessors like the Higher Education Academy, the Institute for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, and (especially) the Learning and Teaching Support Network were designed to support teaching staff in reflecting on and enhancing their own practice.

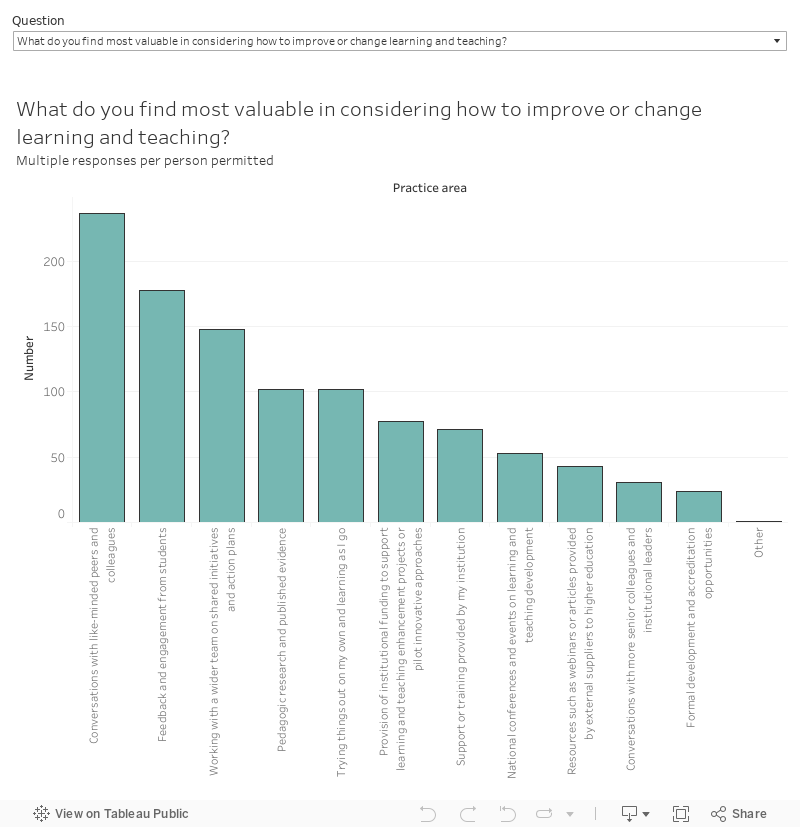

Though some of the networks still persist, and support often comes from subject associations and professional bodies, we don’t really have that kind of UK-wide learning and teaching infrastructure anymore. In England, we have also lost the feedback from peers that came via QAA inspections. So where do academics get inspiration and support for learning and teaching practice?

Our sample (63.9 per cent of them, at least) reported that conversations with like-minded peers were most likely to be of use, above feedback from students (48 per cent). Institutional support was well down the list (19.1 per cent for structures, 20.8 per cent for funding streams) – investment here has fallen sharply since universities used to be directly funded to support this work (via the Teaching Quality Enhancement Fund in England, for example).

Our sample – perhaps because it was self-selecting – tended to report strong personal engagement in learning and teaching development and enhancement, but were slightly less likely to be able to point to a departmental culture that supported this, or an active community of peers, or provider support.

The free-text comments suggested a focus on research rather than teaching and a general air of exhaustion and time pressures as the stumbling blocks here. Some noted a potentially harmful “technology first” approach within institutions:

My concern about new digital technologies is that they seem to be designed by tech people and not lecturers with student input. Therefore there are often significant problems with how they work. I also think the burden on lecturers constantly having to learn new technologies is too much.

A question of resources

More than seven in ten (71.7 per cent) survey respondents strongly agreed that it was reasonable to expect access to core digital resources to be provided to students without additional costs. The consensus (79.2 per cent) was that digital learning resources would increasingly come to dominate, with a corresponding drop in the acquisition and use of hard copy materials.

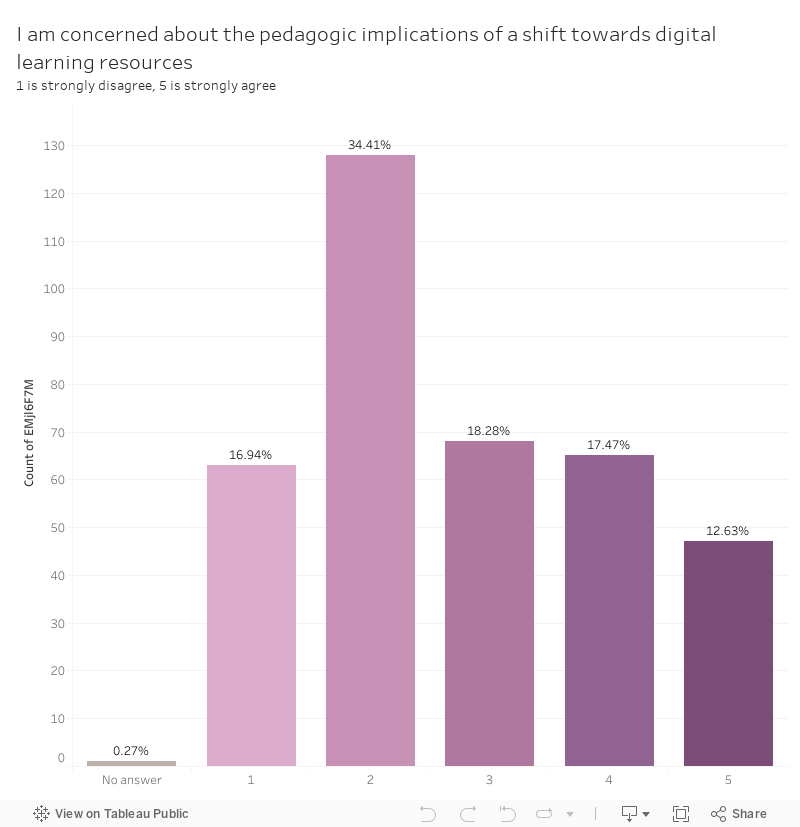

However, this wasn’t uncritical acceptance. More than three in ten (30.2 per cent) of our sample either agreed or strongly agreed they had concerns about the pedagogical implications of a shift to digital resources, a sizable minority when compared to just over half (51.5 per cent who disagreed or strongly disagreed).

The views expressed in free text were very varied. We saw a full spectrum from those who felt that digitally enhanced learning was so ubiquitous that speculation was meaningless, to those that asserted that face-to-face tuition was superior in nearly all cases. In general, we saw the kind of informed scepticism that we may have hoped for – as one commenter noted:

We do need to ensure however, that we do not just create a repository of digital resources that students do not engage with, and that we encourage use of collaborative notetaking, personal notetaking, question and answers on a range of digital media

Interestingly, there was a roughly equal split between those who felt senior leaders (33 per cent) and individual academics (30.7 per cent) should have agency in providing digital resources, with a further 22.9 per cent giving librarians primary responsibility. Of course, all three of these will (and should) have some say in decisions about resources.

A point of inflexion

We’re at a liminal moment in the life of digital learning. Recent practical experience has both proved that it can be done (at a cost) and suggested that the kinds of “revolutions” predicted by some over-excited commentators are wide of the mark. Many respondents picked up on the disconnect between the institutional willingness to learn from and incorporate the best of emergency online provision to meet the increasingly diverse demands of students and the current governmental messaging on the primacy of face-to-face and a need to return to “normal”.

Our micro-commission last year highlighted that there is work to be done on access to and use of digital resources before we can start thinking about the mainstream. The academic voice we heard through this exercise backed this realism up. There are clear affordances to digital provision of all forms – though no single mode of content delivery or collaboration will ever work for all students, all of the time. The near future, like the recent past, is blended – and as the sector gets better at blending we will iterate closer to the sweet spot that supports staff in supporting student learning.

But we can’t ignore the political angle. Ministers, backed by some academics and some students are keen to see a return to “traditional” delivery and are putting pressure on providers to deliver even where this may cut across the interests of good teaching and a good student experience. The sector is – and in living memory, has been – more diverse than policy makers or commentators often understand. We’ll need a range of approaches to ensure that everyone gets the benefit of higher education.

By David Kernohan, Acting Editor of Wonkhe.