In the aftermath of the emergency online delivery that has characterised much of the Covid-19 pandemic, universities are asking serious questions about learning resources.

The problem that everyone from the library to the strategy office is facing is that the data on how students feel about the shift to online resources, and the quality and utility of these approaches, just isn’t there.

By David Kernohan, Associate Editor of Wonkhe.

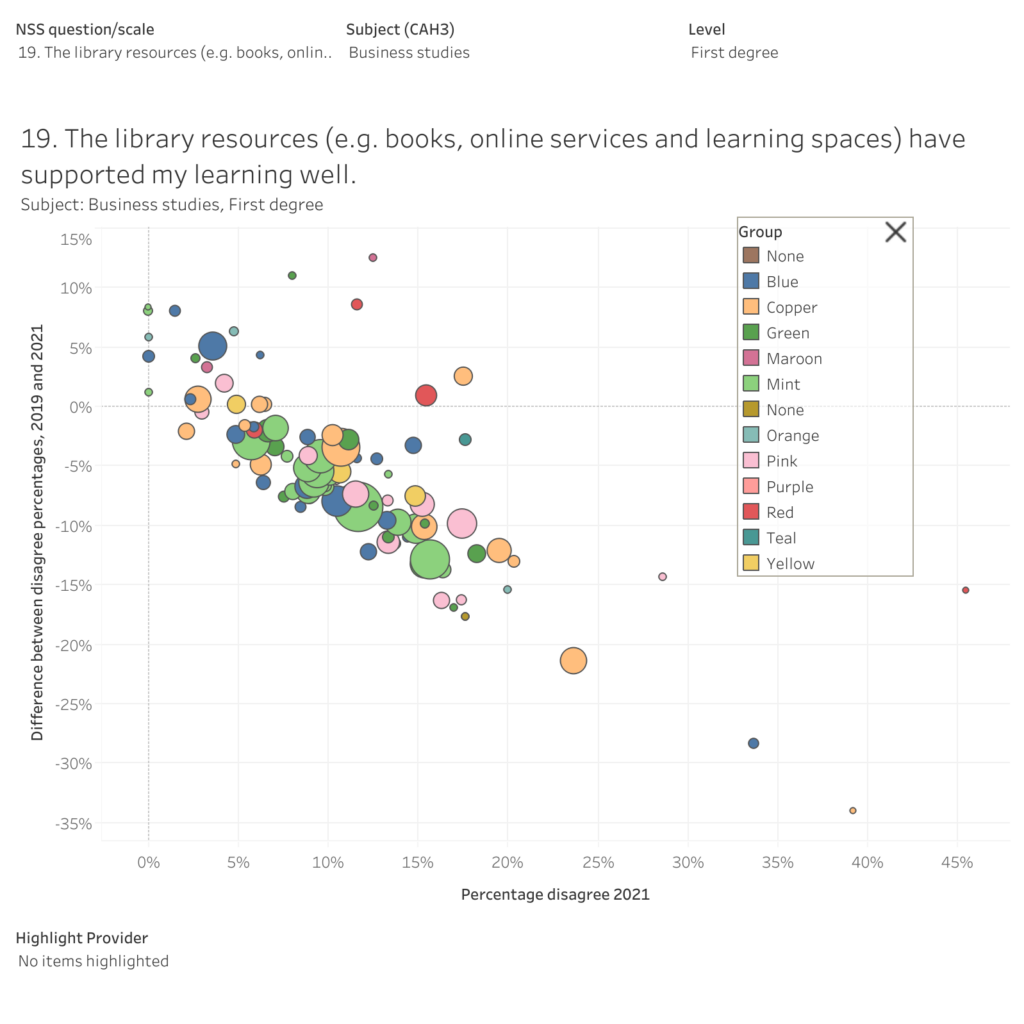

The closest we get in public data – useful if you want to benchmark against the opinions of students at other providers, is question 19 of the National Student Survey. Though it is great to have the importance of learning resources recognised in this survey, the statement for response as written:

19. The library resources (eg books, online services, and learning spaces) have supported my learning well

covers a lot of ground. If you couldn’t get a place to work in the library the week before your exams, or the one time you went to get a book it had been checked out, this is captured in this question. And so is how you feel about online services – which could mean anything from wireless connectivity to the way the VLE works on your phone browser.

What’s in the NSS?

What is there in the NSS makes for concerning reading. Those with high levels of disagreement to question 19 in 2021 are not those that have always struggled. In many subject areas and providers, mass dissatisfaction with the library offer is a new and worrying problem.

The y axis shows the difference between the proportion of students dissatisfied (scoring 1 or 2) in 2019 – the last “normal” year – and 2021, and you can see the full three year trend in the tool tip. The x axis shows the proportion of students dissatisfied in 2021. You can choose subject areas (CAH3) or questions and scales in the NSS (the default is Q19) using the filters at the top, you can find individual providers using the highlighter at the bottom.

Using the data

The typical response to a bad year for NSS is to solicit an enhancement plan from the offending academic department or professional team. In this case, there’s probably something else going on, beyond the scope of a single team to address.

However concerning the data looks, in a normal year it would be supplemented by feedback and focus groups in the library itself. The closure of most library buildings for large parts of the year mean that – despite the sterling efforts of library staff, this informal information has been more difficult to gather and interpret just as it has become essential to put NSS results in perspective.

The pandemic has caused seismic shifts in learning and teaching – including to student engagement with learning resources. Whether these changes will be sustainable, and the medium term impact they will have on student expectations of learning resource accessibility and integration into emerging digital learning environments remain to be seen. And it’s clear that there’s a lot more work to be done to understand how students are experiencing those changes.

Spotlight on Aston

I spoke to staff at Aston University library about this – but really any provider would share the same story. At Aston – a medium-sized provider with strong local roots and a focus on vocational higher education – there was an interest in ebook-first procurement a long way before Covid-19. The onset of the pandemic was matched by a number of “free” offers from publishers and platforms that allowed for experimentation and replacement, but when the offers ended there was a need to secure additional funding from the provider.

Library services were very much in the spotlight at the time the decision was made to provide this – the library was a central feature of university student communications, and staff did their utmost to ensure that students could seek support and advice where it was needed. The additional funding has allowed the team to secure resources the coming year from publishers and aggregators, but the team faces the future. With all of the issues that readers will be well aware of regarding securing electronic copies of books.

Libraries have never been able to meet student demand with hard copies, online resources at least offer a chance to do this if the cost and license is right. At Aston what they know about the student response suggests that learners are positive about this development – networks of student reps and informal feedback suggest as much, though again we don’t know for sure. Certainly, nobody is clamouring for a return to the days of students buying their own books (a trend now largely confined to a few postgraduate courses in Aston, though the size of the direct-to-student market in the UK is still substantial).

Costs, concerns, and changes

All indications are that academics and students are broadly positive when it comes to online resources – as liaison librarian Nicola Dennis put it:

The academics have shown a lot more confidence in eTextbooks due to the positive student feedback. The negativity regarding not being able to have access to a book title diminished and anecdotal comments suggest that students are more engaged with the study materials and using them interactively in conversations with their lecturers.

But academics are also interested in the cost implications – the few who have taken on the US model of building a module around a single (expensive) text generally learn quickly the implication of a decision like this – although the increasing habit of publishers to sell direct to academics is concerning.

And, fundamentally, some subject areas pose more issues than others. In law and medicine it is most important to have access to the most up to date resources – in business it is the number of simultaneous resource accesses that causes concern. Humanities and arts subjects are generally not well served with online resources – it is harder to identify materials that are useful to students.

Within these macro trends, resource usage data can help to understand particular student needs. As e-resource library specialist Erica Lee told me:

Investing in eTextbooks was something we’d always wanted to do for our students, and now that we’ve been able to do it, the engagement we’re seeing shows us how valuable that content is. Students are making the most of features like searching within the text, along with highlighting and annotating, and this is helping them to get the best out of the material and engage with the topics they’re studying.

Thinking longer term

Libraries did an incredible job during the worst days of the pandemic – and the effects of the changes made during this period will be felt for times to come. However, there is no national understanding of precisely what is happening – the NSS question is broad, and a negative trend lining up with student frustration with many other worries hides what appears to be immense positivity about accessing resources online.

This year the sector faces a new iteration of NSS with – most likely – an updated version of the learning resource question. Rather than going through the usual NSS review-and- enhancement procedures, it could be a good time to suspend judgement, and consider what the longer term future for provision and integration of learning resources is likely to be.

The development of this article was supported by Kortext

By David Kernohan, Associate Editor of Wonkhe.